Listen now

Over the past decades, cloud infrastructure has become a critical backbone for the modern software stack. Only for cloud IaaS/PaaS (Infrastructure-as-a-Service, virtualized computing or storage servers, or Platform-as-a-Service, ready-to-use platforms for building and running applications), the global spend is already surpassing $400B in 2025 (Gartner), and growth has not slowed with size. For IaaS and PaaS, CAGRs have been between 20-30% from ’23 to ’25 (Gartner estimate), as AI training and inference, data-heavy analytics, and modern application delivery pile into the cloud.

In the 2010s, a handful of providers, namely AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud, started the growth trend by building end-to-end cloud stacks and turning scale into dominance. Although today these hyperscalers look similar, initially their playbooks were very different. AWS spread bottom-up as developers could start with a credit card and pull the enterprise along; Microsoft won top-down through enterprise sales, bundling and licensing constructs; Google Cloud differentiated with its data/ML tooling and attractive discounts and other offers. However, they all had the same goal: they stitched together a global network of data centers, layering on managed services and developer ecosystems. Scale enabled higher margins, while reliability, security certifications, as well as strong partner ecosystems made them the default choice for new enterprise-level applications. Above all, the convenience from having all cloud-related services from a single provider was a key driver for customer value.

As customers concentrated spend on these integrated platforms, ultimately the leaders captured over two-thirds of the global cloud market. The flywheel was straightforward: launching more services pulled in more workloads; more workloads created more data in their clouds; that data gravity attracted more customers and justified even more investment in infrastructure, cementing the hyperscalers’ position.

New customer needs driving the change

Now a new trend is visible in the cloud market: the center of gravity is shifting away from a single-provider default towards different multi-cloud approaches, enabling challengers to gain momentum. Venture funding into cloud infrastructure and SaaS was roughly $50B in Europe and US in 2024, and the growth of AI is only increasing interest in new entrants. Some of the recent mega-rounds include CoreWeave’s $1.1B Series C, Lambda’s $480M Series D and Crusoe’s $600M Series D.

There are many factors behind this change. Firstly, AI is raising the demand for compute. Training and serving AI models demands dense GPU clusters, high-bandwidth memory, low-latency interconnects, and far more power per rack. That pushes providers to redesign data centers, adopt custom silicon, and source capacity beyond traditional providers. On the other hand, this part of the infrastructure is one of the most difficult ones to forecast: supply has been and will be allocation-constrained, while demand is being shaped mainly by mega-contracts like OpenAI’s reported $300B, five-year deal on Oracle Cloud.

At the same time, end customers are more price-aware and less tolerant of hidden costs. Discounts have traditionally been exchanged for long-term commitments and spend thresholds, rewarding staying and penalizing leaving. Combined with egress fees—meaning charges for moving data out of the cloud—and proprietary services, the lock-in effect of hyperscalers is strong. This is now driving customers to consider alternatives, as hyperscalers are still unlikely to cut prices or eliminate additional fees. Clearer pricing and data portability are now the way to win business.

A more recent trend is the focus on data sovereignty globally. Customers’ needs have shifted from “best-effort compliance” to hard guarantees. They want data to stay in-country with providers that know local regulation. Procurement now often needs proof over the full lifecycle of the data: where does it live, who can touch it, who holds the encryption keys, how are incidents handled, and how is data cleanly exited or deleted. Even if hyperscalers are setting up local subsidiaries, the trust on large multinationals in this regard is declining: Microsoft France itself even admitted it cannot guarantee data sovereignty. While the CLOUD Act has been making headlines for conflicting with GDPR in EU, it undermines data sovereignty in other countries outside of Europe as well.

A final key driver is the continuing trend for multi- and hybrid cloud. End users spread workloads across providers to improve resilience, performance, and procurement leverage, while keeping certain systems on-premise for control or latency. In a similar manner, as applications like IoT, real-time AI inference, AR, and autonomous systems require storage and compute to sit closer to users and devices, edge and distributed cloud are becoming more important. Historically, for traditional enterprise apps, multi-cloud approaches often proved too costly and complex, and dividing workloads across clouds also made the customer lose part of the end-to-end integrated offering value. AI and data workloads change that calculus: they’re more modular and portable, so teams can keep models and data platforms cloud-agnostic and place training/inference where price-performance and capacity are best. Today’s mature tooling—containers, orchestration, infra-as-code, and independent observability, for example—also makes this mix practical at scale.

IaaS: a game of specialization and cost advantage

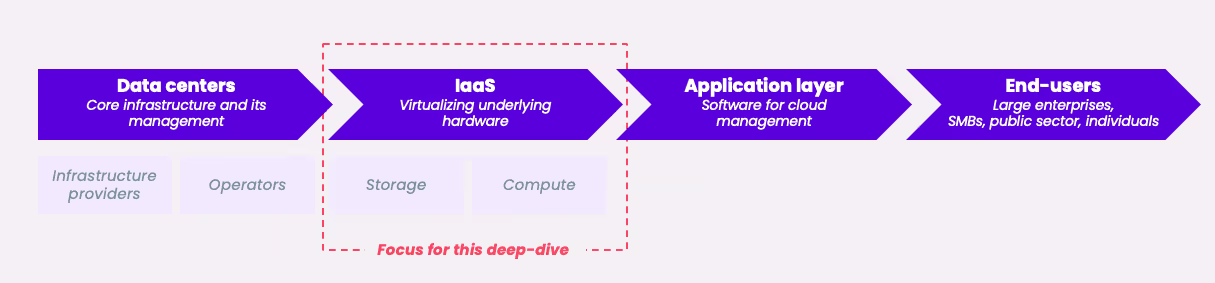

Having covered how we got here and why change is accelerating, we now detail the key shifts reshaping the cloud value chain, focusing on Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS).

Compute- and Storage-as-a-Service have always been the core products for hyperscalers, allowing for a broad offering of applications and end-use cases. Now, new customer needs are emerging, especially for the IaaS layer, giving more space for specialized players to emerge.

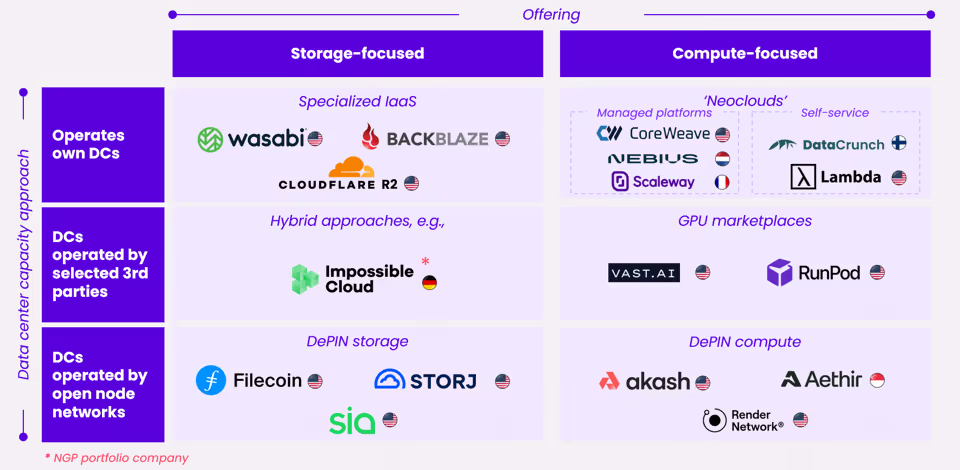

These new entrants cluster into two lanes—storage-focused and compute-focused—built on three approaches to build out data center capacity. First, companies that run their own data centers aim to maximize control over their infrastructure, which suits large, latency-sensitive or GPU-dense workloads. However, all of this requires heavy CAPEX and time to scale capacity, not to mention a global footprint. On the other hand, IaaS providers that outsource the data center operations to selected third parties scale faster, while trading off some dependency on supplier capacity and pricing. Finally, some players decide to build supply on top of an open network where anyone can offer capacity, following the principles of DePIN projects for decentralized ownership, cost-effectiveness, and tokenization. Here, a common downside is the loss of control over hardware, as there are often no limits or requirements on who can offer supply.

These approaches create differentiated segments within the market for new cloud entrants. On the storage side, specialized IaaS providers are gaining share as they are tailoring narrower offerings to customers’ exact needs. S3-compatible platforms with lower and simpler pricing (often low or no egress) let teams store hot, warm, and cold data according to their needs, keep procurement predictable, and avoid vendor lock-in. Key players, such as Wasabi, Backblaze, and Cloudflare are all US-based and have been in the market for years, meaning that ultimately the fragmentation in this segment is still rather low. This is partly due to the challenges with scaling data center capacity.

On the other side of the spectrum is the constantly evolving landscape of DePIN storage and DePIN compute projects, where heterogeneous operator pools can create new capacity fast but carry the risk for inconsistent performance. For storage, more established players, such as Filecoin and Storj, operate at high capacity with sustained paid utilization, whereas for compute, the networks are still ramping up, report smaller active capacity and volatile usage patterns. Overall, these offerings are often more tailored towards individuals or SMEs, as they tend to lack enterprise-grade compliance, support, and quality.

NGP’s portfolio company Impossible Cloud is a great example of a hybrid approach with their decentralized hardware provider network packaged as a single enterprise service and distributed by a network of resellers, MSPs and traditional distributors. Their unique approach takes the best elements from both worlds: customers get lower, more predictable TCO without sacrificing security or compliance, while the network of carefully selected and vetted hardware providers is easier to scale. Impossible Cloud operates through two entities. There is the company itself, which provides one S3-compatible endpoint for hot object storage with unified SLAs, support, billing, and observability for a variety of end customers and needs. In addition, there is the Impossible Cloud Network, a nonprofit foundation that is focused on building the web3-based tokenization for the hardware providers.

Impossible Cloud’s focus on storage allows them to offer high performance, meaning speed and reliability, something that is not a given for newer entrants in the space. Due to their data center approach, they can also provide this high-performance storage at a much lower cost and CAPEX compared to hyperscalers and other players operating their own data centers, while their effective channel partner approach and truly enterprise-grade offering differentiate them from most DePIN projects. In addition, Impossible Cloud is able to cater to the growing concern of data sovereignty with its European data center capacity (currently in 5 countries) and knowledge of local regulation. This also applies to countries outside of Europe, as Impossible Cloud can credibly deliver true data sovereignty across multiple jurisdictions globally as a European company. At NGP, we believe that this mix of enterprise-grade sovereign storage offering, cost advantage, and rapid scaling of data center capacity will allow Impossible Cloud to continue their remarkable growth trajectory.

On the compute side, neoclouds and are a new class of cloud providers that focus on offering specially optimized GPUs with developer-friendly UX and pricing, rather than offering a broad variety of general services like the hyperscalers. GPU marketplaces operate for similar end-use needs but focus on aggregating capacity from several sources and allowing users to rent it on demand. In practice, both usually complement the big cloud providers rather than replace them—teams often keep data and many services on a hyperscaler, but switch to a smaller player when they need access to compute fast or for specific workloads. In any case, the model is working at least for some players: CoreWeave, one of the leading neoclouds, has grown into +$3.5B of revenue, signed a +$10B multiyear deal with OpenAI, and became one the largest tech IPOs in the US in 2025.

On the other hand, the business model is not risk-free either, and many emerging startups have had challenges in scaling. Hardware supply is and will be tight, customer concentration is often high, and pricing can be volatile. The market is also becoming more saturated: even though companies slightly differentiate in their key focus on bare metal vs. VM vs. serverless offerings, there are already many somewhat similar existing players aiming to tackle this problem.

Looking forward

Even though the cloud market is still dominated by hyperscalers, signs of change are already visible and accelerating. Cloud is the execution layer for modern software, so every major shift—AI hardware, data regulation, cost pressure, and edge demand—will continue reshaping infrastructure choices and consequently the broader market.

In case you have any thoughts on this change, or you are a founder in the space, please do not hesitate to contact me at sanni@ngpcap.com!

Contributors:

Ossi Tiainen (Partner, NGP Capital)

Markus Suomi (NGP Advisor)

.svg)

.avif)

.svg)

.avif)