Listen now

On a crisp January winter morning in Copenhagen, Christian Tang-Jespersen, the former CEO of Heptagon, and NGP Capital's Bo Ilsoe, a major investor in Heptagon, sat down to share the behind-the-scenes story of Heptagon for the first time.

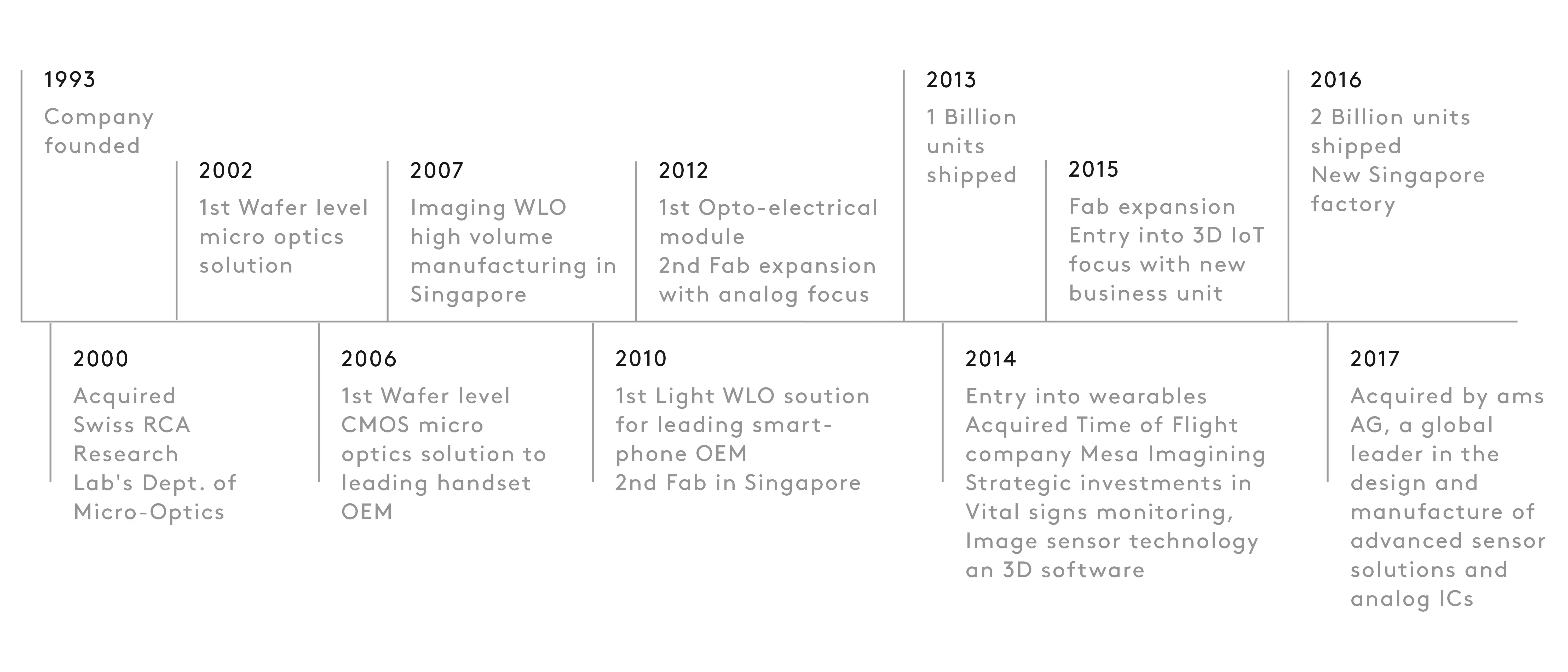

The story of Heptagon begins in 1993 when a team of researchers spun off a university project in Finland and started a new business around micro-optics. Business was slow, and the first product would only see daylight nine years after the conception of the company after the team acquired a wafer optics lab in Switzerland and opened and engineering site in Zürich. However, once the product was launched, the path to global profit looked clear. Success struck fast: in 2006, NGP Capital made its initial investment in the company and simultaneously brought Heptagon its first big customer: Nokia.

Although Nokia was a big client, it soon became apparent that Heptagon had placed all their eggs in one basket. Being dependent on a single large customer and having a strict focus on one product category started to rock the boat in 2009. Hit with the shock of the financial crisis, the entire tech industry was at risk of failing. For Heptagon, it meant trouble. Buyer volumes shrunk month by month. The appetite for wafer-level optic lenses — Heptagon’s main product — started diminishing and investors raised concerns about the company’s management’s response to the crisis. Manufacturing lines ground to a halt.

By that time, Bo had worked systematically on a heavy recapitalization of the company and had beefed up the investor syndicate by inviting several strong investors including GGV Capital, who sent Kheng Nam Lee to step in as the new chairman of the company, and Temasek from Asia to join as co-investors. NGP Capital had simultaneously been pitched to by Hymite, a small wafer packaging company based in Singapore run by Christian, a Dane who was familiar with the semiconductor industry. Although Bo never invested in Hymite, he introduced Christian to the investors of Heptagon in hopes of introducing new thinking into Heptagon’s business. Something clicked. When Christian sold Hymite to TSMC and had packed him and his family’s belongings into cardboard boxes, bound for his native Copenhagen, he was offered the reins of Heptagon.

BI: I was immediately impressed with Christian and thought he could be someone whose perspective we could really use given that he had dealt with large OEM customers in his previous roles and was close to the semiconductor industry.

CTJ: I had met with the Heptagon team and with some of the investors a couple of times to give some advice on the company, and we had stayed in touch since. I knew how bad things were at the company, but was compelled by the team. Ultimately, I could not figure out why such a unique technology, verified by Nokia, could not be more in demand! I had grown fond of the core team at Heptagon; they were skilled, reliable, and willing to make this work. So, I told my wife that this wouldn’t be a journey that would last for longer than two years. It was clear that either we had to merge with someone who could pick up the technology or we had to cut costs and sell everything fast.

“I knew how bad things were at the company, but was compelled with the team and ultimately, I could not figure out why such a unique technology, verified by Nokia, could not be more in demand!”

At the time Christian joined the company, it had a revenue run rate of $25M. During his first year spearheading the company, they, as he describes it, “lost an enormous amount of cash every month”. The CFO at the time had already prepared a draft chapter 11 filing which he presented to Christian during his first week on the job. The company’s biggest customer at the time was Nokia, and money was being lost by the hour since the company was unable to make any money on the product margin. A large section of the team had to be let go of — it was a rude awakening in many ways.

CTJ: Basically, we were going out of business. I had to let go of a large amount of the team during my first months. It was quite a blow. Literally, no-one was convinced that the company would survive as a standalone. I could only focus on stopping the bleeding and did not have much time to look towards the future. That was our reality. At the same time, in the back of my mind, the same question kept bothering me, “If no one else can build this technology, how can we not redesign our business model making it commercially sound?”

From struggle to struggle

In 2010, Christian’s first year on the job, Nokia put front-facing camera lenses — Heptagon’s specialty — in their phones, but customers hadn’t yet bought into the idea of capturing photos with a front-facing camera. There was no pride in being a market leader for a feature consumers did not see as a necessary addition to their devices. The financial struggles at Heptagon continued and the company could barely stay afloat. Changes had to be made. Heptagon moved its staff to Singapore to be closer to the manufacturing lines and had to implement changes into the roles of the team, too.

“CTJ: We found ourselves in a situation where we were making market-leading technology but not a single market-leading product. They were just nice-to-haves, not need-to-haves, so we didn’t earn much on the dollar and, honestly, our confidence reflected this.”

Apple’s launch of FaceTime made consumers go wild for front-facing cameras, but, although the attitude switch in the market benefited Heptagon, they knew they could not compete in the technology war on imaging lenses in the long run. Something had to change. Manufacturing lines ground to a halt again in 2012, this time to make a move towards developing lenses for LEDs, flashes, light sensors and an array of other products that rely on the core wafer level technology. However, the company’s struggles were far from over. Another leaf in the company’s book was turned.

CTJ: We were hit differently this time. The assembly lines run by other companies were not able to deliver on what our technology and products could actually do. Eventually, we said, why don’t we try to build the packaging around the lenses and morph our systems to provide not just the optical lens, but also the assembly, all built on our high level of precision and performance? That was the single most important decision we made in Heptagon’s turnaround story. It almost felt like a coincidence at the time, but it ultimately made strategic sense to move up the food chain and control more of the system.

From deep despair to two billion shipped units

By 2016, Heptagon looked very different from the company Christian had originally joined. The company had shipped a mind-boggling two billion units, had around 2000 employees on their payroll and had opened a gigantic 300,000-square-foot manufacturing site in Singapore to answer to the demand of almost a million units per day. It was both a financial upturn as well as a tangible rise in the company’s morale. Christian was finally able to prove his original hypothesis: the product was good and customers wanted to pay for it.

CTJ: Another epiphany we had from talking to new clients was realizing that no-one could do this better than we could, and the customers were willing to pay a premium for it. We went from an average selling price of around 10 cents per unit to more than 50 cents per unit in less than two years and, for us, it was an astounding accomplishment as we suddenly could see a path to profitable growth. More importantly, the customers were still willing to pay and were looking for innovation in their product portfolio that our technology enabled. We started building bigger systems and took more responsibility for the technology around our lenses. When we landed a new, giant customer, willing to pay well over a dollar per unit, a new era started at Heptagon and business really picked up. We had ultimately reshaped from being a pure tech company to become a product-focused company. The benefit of this was obvious — we suddenly had a very clear direction and our investors’ trust in us during the rough times was now starting to pay off.

In 2013, the company raised a whopping $270M round, which in line with its media-shy profile, was never announced. Although one would expect a CEO to want to shout their success from the rooftops, Christian had made a conscious decision to avoid media appearances and interviews that he stuck with even when the company was experiencing triumphant success. He simply didn’t feel like that sort of publicity would have benefited the company nor its team. Having acquired battle scars from the dot-com days, he had seen first-hand how damaging it could be for the company mentality, too. He still doesn’t feel that it’s realistic to just celebrate the good times unless you are prepared to recognize the down-turns. At the end of the day, the company simply wanted to focus on the business. Nothing else mattered.

CTJ: I still remember when we shipped our first billion units. I think it was the first thing we ever actually announced. It was a significant milestone. We had shipped a billion units, something not many had done, right? This was real news as it pertained to our products. We had gone from deep despair to rebuilding the technology, the team, and the whole company. We had adjusted to new market conditions, built up team confidence, and shipped high volumes. Going from focusing on the technology to focusing on the product really changed us. We were also quite focused when it came to budget spend, having been through such hard times. We were not frugal, and certainly never cheap. We just always spent money in a way that made sense. We didn’t buy expensive furniture or design, nor market the company. We simply focused on the business and invested both into it and the team. One year, we gave $10M back to the employees as an extra bonus. I just sent an email to our entire workforce saying they all had two years of extra salary in their accounts now, as an act of gratitude by Heptagon. That was it.

“We had gone from deep despair to rebuilding the technology, the team and the whole company. We had adjusted to new market conditions, built up team confidence, and shipped high volumes. Going from focusing on the technology to focusing on the product really changed us.”

A culture built on acceptance

The exit came in 2017 when Heptagon was sold to ams AG, an Austrian microelectronics company listed in Zürich, Switzerland. It was a natural move. Heptagon was the undisputed market leader but was at a stage where it would have had difficulties to find new ways to grow further without making significant changes. Steep growth required even larger investments, and the time was right to take a step into something bigger that would complement the core technology of Heptagon. Ams AG was the perfect remedy for the situation.

CTJ: The core team that I started with when I first came to Heptagon was there with me at the time of the exit. Going through all of this with the same people was a wonderful experience. We built a common understanding and a high degree of comfort as we navigated both good and bad times. As we developed the company, we worked hard throughout our whole journey to create the Heptagon culture, which was grounded in a common decision to stay focused on what mattered. If any politics, gossip or divergence emerged, we immediately made it clear that we did not want nor accept it. We had a clear vision of how we wanted to be. I also forced myself to make fast decisions. If we hired the wrong people, we had to let them go within six months for the good of the company. You need to stay practical, rooted and focused to be able to manage the complexities of growth like this.

Sometimes growth also requires self-sacrifice. Self-assessment, a sometimes rare trait among CEOs, was practiced by Christian throughout the process, as he insisted on a continuous assessment of his capacity in the role of the CEO of a high-growth company. This transparency and critical approach was just a part of the company culture of Heptagon. All in all, Christian cultivated a mentality of willpower: turning something that can be seen as a fault or flaw into something that can be utilised to advance your dreams and strive for better every day.

CTJ: As a CEO, you need to be very realistic and ask the hard questions about whether you are the right person for the next step of the journey. Not every CEO is good in every situation. Not everyone excels at all stages. You need to be conscious of that and frequently ask yourself: am I the right person to take this to the next level?

BI: I was always surprised and impressed by Christian’s ability to handle problems and setbacks in a calm and collected way. He is very analytical about problem-solving but always employs a keen eye for doing what is right for his team. I think his legal training often kicked in, allowing him to separate rational analysis from emotional bias.

CTJ: There are several things that have shaped my management style. One of my first bosses was a young counselor for a listed company. He was part of the management team and had a law degree – and he was dyslexic. He literally could not spell one word correctly. But he never let that get in the way of his plans. That fascinated me, because, at the end of the day, it’s all about willpower: turning a weakness into a strength or even just ignoring a weakness completely. That really struck me and stayed with him. He was smart, open and conscious, but never used his weaknesses as an excuse. We all have weaknesses, but it’s really about how you manage them. Do you let them block your route or not?

“We all have weaknesses, but it’s really about how you manage them. Do you let them block your route or not?”

Finding success is also about taking things as they come; looking for new routes and switching your mindset when the circumstances around you are not malleable. Staying calm, thinking rationally and being open to new solutions is likely to yield better results.

CTJ: Another rule I live by is to focus on the things that you can affect and ignore the ones you can’t. If you can’t change it, just accept it and let it flow through you. When things were rough at Heptagon, my team would often look at me, saying, “Christian, you should be panicking right now!” But I didn’t. It didn’t mean that I was not invested, I just felt that panicking would not help, so what would be the point? My team made me strong. The idea that we would make this happen or burn together really glued us together, and it still binds us today. It made us stable as a management team, which then led to the rest of the company feeling that stability around us. I have always driven a full transparency policy when it comes to the board. It was a bit uncomfortable in the beginning as our board had members from different nationalities, and this transparence was an unusual approach for some people. But it built a foundation of trust. We could always have a very open dialogue. It made us more willing to take risks.

Life after Heptagon

The core team at Heptagon often joke among themselves by asking if they’re allowed to leave now. They always had an implied agreement that, as part of the team, they could not abandon the others. There were multiple chances to give up and sell the company along the way but the team was mindful to focus on the right fit. Even when the times were good and high offers were on the table, they chose to wait until ams AG came along. But for Christian, exit doesn’t mean laying his career to rest.

“There were multiple chances to give up and sell the company along the way but the team was mindful to focus on the right fit.”

CTJ: I don’t think I will ever retire from technology and business. I’ll only quit when no one wants my help anymore, which I hope won’t happen anytime soon. It’s hard to figure out how to give back, though. Now I spend about a fifth of my time investing in cancer research. On top of that, I spend time promoting great technology achievements that we continue to develop in Denmark, in Scandinavia, and in Europe. There is a lot to be thankful for coming from there. I also work with a lot of startups that are moving into a mid-growth stage by helping them benefit from the lessons I learned at Heptagon. Our leadership team and board of directors amassed many learnings throughout our journey. We are all pleased to be able to spread that knowledge and help others that are going through similar situations with their companies.

.svg)

.svg)